Today for Fae-tastic Friday we’re going to wrap up our mini-series of guest blogs about changelings. This final posting is about Lady Wilde, who I’m a little chagrined to admit, was never on my radar before reading Shannon’s blog. Whether you’re in the same boat as me or you’ve read the Lady Wilde’s work before, I hope you will enjoy this last entry into our series on changelings 🙂

Lady Wilde and the Fairy-Haunted Hills

by Shannon Phillips

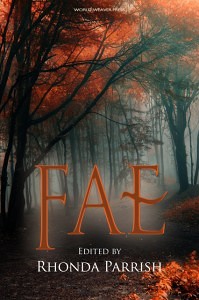

![By Frank Harris [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://rhondaparrish.com/archive/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Speranza-wilde-mother.png)

Her book of Irish folklore, first published in 1887, gives us a snapshot of traditional Irish culture at a time when it was just beginning to yield to modernization. “In a few years such a collection would be impossible,” she writes in the preface, “for the old race is rapidly passing away to other lands, and in the vast working-world of America, with all the new influences of light and progress, the young generation, though still loving the land of their fathers, will scarcely find leisure to dream over the fairy-haunted hills and lakes and raths of ancient Ireland.”

Although in that, I think she was wrong—many of us are still dreaming of fairy-haunted hills! One of the reasons I think her book is so valuable, though, is that it reminds us that originally these stories weren’t just “stories”: fairies, spirits, and changelings were considered very real in Lady Wilde’s day. And these were matters of life and death.

On the question of changelings, Lady Wilde writes:

“This superstition makes the peasant-women often very cruel towards weakly children; and the trial by fire is sometimes resorted to in order to test the nature of the child who is suspected of being a changeling. For this purpose a fairy woman is usually sent for, who makes a drink for the little patient of certain herbs of whose power she alone has the secret knowledge, and a childless woman is considered the best to make the potion. Should there be no improvement in the child after the treatment with herbs, then the witch-women sometimes resorts to terrible measures to test the fairy nature of the sufferer.

“A child who was suspected of being a change because he was wasted and thin and always restless and fretful was ordered by the witch-woman to be placed for three nights on a shovel outside the door from sunset to sunrise, during which he was given foxglove to chew, and cold water was flung over him to banish the fire-devil. The screams of the child at night was frightful, calling on his mother to come and take him in; but the fairy doctor told the mother not to fear; the fairies were certainly tormenting him, but by the third night their power would cease, and the child, would be quite restored. However, on the third night the poor little child lay dead.”

So there is a kind of terrible sadness behind the changeling legends. Not just Come away, O human child / To the woods and waters wild… but real lives, real children rejected by their families or even tortured to death in a doomed attempt to “cure” them. It’s easy to think of those in our own society who have suffered misguided interventions because their differences were stigmatized—so called “gender variant reparative therapy” springs to mind, or the autistic children who have suffered abuse in the name of treatment. Maybe we have our own changelings still.

But not all the stories Lady Wilde gives are so sad. In one of my favorite passages, she mentions that when a woman went into childbirth, it was common for the family to go through the house and unlock every chest and drawer. As soon as the baby was born, these boxes and drawers would be snapped shut and locked. The idea was that fairies might try to creep into the house and hide, in order to be ready to steal the baby at the first opportunity—and the family was hoping to trap them!

Other substances thought to have some power over changelings were salt; the branches of a mountain ash (for girls) or alder tree (for boys); the name of God and the sign of the cross; or a nail from a horseshoe. But above all these others: fire. Two unlit coals, one laid beneath the cradle and another beneath the churn, were thought to be sufficient to prevent fairy mischief. Or a lit coal might be drawn in a circle around the cradle, to create a barrier the fairies could not cross. Even the threat of burning was thought to be enough to force a changeling to reveal itself.

Changelings are usually marked by their weakly, wizened forms. But sometimes they are revealed by their preternatural knowledge or abilities. In one story Lady Wilde tells, the father realizes his child is a changeling when the baby picks up four straws to play with: “And when he got them, the child played and played such sweet music on them as if they were pipes, that all the chairs and tables began to dance; and when he grew tired, he fell back in the cradle and dropped asleep.”

And some of the stories contain a seed of hope for bereaved parents. For when a child is stolen by the fairies and cannot be rescued, there is at least the hope that they will have happy lives among the Fair Folk and grow up to be loved by a fairy bride or groom. And as Lady Wilde relates: ” The children of such unions grow up beautiful and clever, but are also wild, reckless and extravagant. They are known at once by the beauty of their eyes and hair, and they have a magic fascination that no one can resist, and also a fairy gift of music and song.”

I’ll give one more changeling story from Lady Wilde. It’s my very favorite, because in this case the issue is resolved when the fairy mother comes looking for her own stolen son. As she tells the parents: “My people, who live under the fort on the hill, thought your boy was a fine child, and so they changed the babies in the cradle; but, after all, I would rather have my own, ugly as he is, than any mortal child in the world.”

So the fairy mother takes her baby back, and gives the mortal parents advice on how to storm the fairy fort and rescue their own son. They follow her advice to the letter, and the outcome is a happy one: “By the spell of fire and of corn the child was saved from evil, and he grew and prospered. And the old fort stands to this day safe from harm, for the man would allow no hand to move a stone or harm a tree; and the fairies still dance there on the rath, when the moon is full, to the music of the fairy pipes, and no one hinders them.”

Shannon Phillips lives in Oakland, where she keeps chickens, a dog, three boys, and a husband. Her first novel, The Millennial Sword, tells the story of the modern-day Lady of the Lake.